The Tip of the Iceberg

People with an interest in political repression in Russia will likely have heard of Yevgenia Berkovich and Svetlana Petriychuk. Some will also have heard of Antonina Favorskaya, Olga Komleva, Maria Ponomarenko and Nadezhda Buyanova.

Yet, these well-known cases represent only the tip of the iceberg. For every well-known female political prisoner, there are a great many others whose stories remain largely untold. And there are a huge number of women who have been victims of political repression about whom nothing is known.

At the present time, the ‘Political Prisoners. Memorial’ human rights project has recognised 72 women as political prisoners, while 266 women have been included in our database as being imprisoned on the basis of prosecutions where there are indications of political motivation. However, we know that our database is far from complete. It includes only those women for whom we have information, however little.

According to our estimates, at least 10,000 individuals have been imprisoned in Russia on politically motivated charges, including no fewer than 7,000 Ukrainian civilian hostages held without the least formal legal justification. Of these, as many as 1,000 are women.

In addition to those imprisoned, it is difficult to assess the number of women who have been victims of non-criminal forms of politically motivated persecution—such as administrative-law charges, searches, arrests, dismissals, expulsions from educational institutions, and threats. Nevertheless, it is clear that this number runs into many thousands.

| Women imprisoned and recognised as political prisoners by ‘Political Prisoners. Memorial’ | 72 |

| Women imprisoned and recorded as victims of prosecutions with indications of political motivation (including those recognised as political prisoners) | 266 |

| Estimated total number of women imprisoned as a result of prosecutions with indications of political motivation | Up to 1,000 |

| Total number of women subjected to politically motivated persecution in various forms | ??? |

Source: ‘Political Prisoners. Memorial’[1]

Repression in Wartime

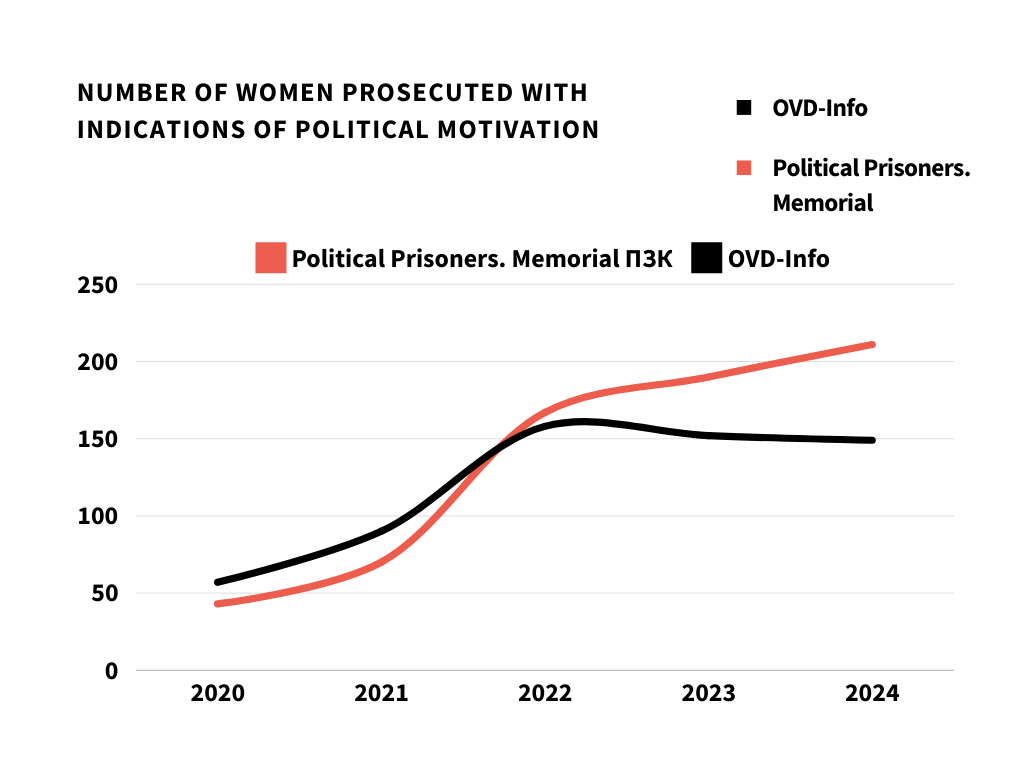

The scale of politically motivated prosecutions has increased sharply since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The number of such criminal cases against women has increased several times over. According to the ‘Political Prisoners. Memorial’ project, in 2024 nearly five times as many women were prosecuted on politically motivated criminal charges as in 2020.

Number of women prosecuted with indications of political motivation (new defendants by year and number):

Sources: ‘Political Prisoners. Memorial’, OVD-Info

The Share of Women is Growing

The share of women among the total number of victims of politically motivated prosecutions, increasing before the war, has continued to rise since 2022. Today, roughly one in five people charged in a politically motivated case is a woman.

Percentage of women in prosecutions with indications of political motivation (new defendants by year and percentage):

Sources: ‘Political Prisoners. Memorial’, OVD-Info

What Charges Result in Imprisonment?

The five most common politically motivated charges brought against women in criminal cases are as follows:

Articles of the Russian Criminal Code under which the largest number of politically motivated prosecutions were initiated against women (2022–2024)[2]

| Article of the Russian Criminal Code | Number of Cases | Share of Politically Motivated Cases Against Women |

| ‘Fake news’ about the army (Article 207.3) | 93 | 16% |

| Organising or participating in an extremist organisation (Article 282.2) | 87 | 15% |

| Public calls to engage in terrorism or justification of terrorism (Article 205.2) | 70 | 12% |

| Terrorist acts (Article 205) | 44 | 8% |

| Discrediting the Russian armed forces (Article 280.3) | 39 | 7% |

Source: ‘Political Prisoners. Memorial’

In the first place, it should be pointed out that nearly a quarter of politically motivated criminal cases against women relate to charges based on laws introduced specifically to suppress opposition to the war. In 2022, just a week after Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the authorities introduced into the Russian Criminal Code the offences of ‘spreading fake news’ about the military (Article 207.3) and ‘discrediting the Russian armed forces’ (Article 280.3). These laws are now routinely used to prosecute individuals for virtually any anti-war statement or action.

The offence of ‘organising or participating in an extremist organisation’ (Article 282.2) with regard to women is most often used to prosecute Jehovah’s Witnesses. Since 2017, when the Russian Supreme Court unlawfully designated the religious group as an extremist organisation, members of this confession have faced continuous repression. In total, since 2017 we know of more than 200 women prosecuted for belonging to this religious group.

‘Public calls to engage in terrorism or justification of terrorism’ (Article 205.2) is broadly interpreted by law enforcement and the courts to apply to various statements. These include expressions of support for Ukrainian military units classified by Russia as terrorist organisations (primarily the Free Russia Legion and the Russian Volunteer Corps), assertions that Ukraine has the right to strike military targets within Russia, and even emotional statements—such as those wishing harm upon members of law enforcement and military bodies, government officials, or Vladimir Putin himself. Most of the women prosecuted for this offence had made statements on social media or other online platforms. In many cases, these statements were seen by only a few dozen people and had no real-world impact, yet courts handed down guilty verdicts, and in many cases sentences that included imprisonment.

A striking, if not typical, illustration of how law enforcement agencies combat ‘justification of terrorism’ is the case of the school student Eva Bagrova.

The Case of Yeva Bagrova

Yeva Bagrova, a resident of St Petersburg, was born in 2008 and was a high school student at the time of her arrest. On 27 December 2024, she was detained and charged with ‘justifying terrorism’ (Article 205.2, Part 1) after she had put up, on a school noticeboard, photos of Denis Kapustin, founder of the Russian Volunteer Corps, and Aleksei Lyovkin, another member of the group, with the caption ‘Honoured Heroes of Russia.’

The photos remained unnoticed for several days before someone called the police. The next day, the school student was arrested. She was charged with ‘justifying terrorism’ and remanded in custody. If convicted, Bagrova faces up to five years’ imprisonment.

There are great differences among women ‘terrorists’ in Russia today. Some are teenagers who, in exchange for a reward, agreed to set fire to a railway relay cabinet. Others are elderly women misled by phone scammers into thinking they were assisting Russian security services in covert operations. Yet others have been entrapped by Russian security services.

The acts attributed to these women do not meet the legal definition of terrorism and, in most cases, pose no real threat. However, this has not stopped the authorities from bringing charges of this kind and handing down fresh convictions. The number of terrorism cases under Article 205 with indications of political motivation brought against women is increasing every year. In 2022, we identified six women who faced such charges; in 2023, that number had risen to 16; by 2024, it had reached 22.

An illustrative example of this kind of ‘terrorist attack’ is the case of Valeriya Zotova.

The Case of Valeriya Zotova

Valeriya Zotova is a resident of Yaroslavl, born in 2003. She worked in the local warehouse of Magnit, a retail chain. Before the full-scale invasion, Valeriya’s mother had gone out on single-person pickets supporting Aleksei Navalny and Sergei Furgal. In November 2022 she was fined for discrediting the Russian armed forces. Valeriya herself also condemned the invasion of Ukraine and, probably as a result of this civil society activity, the two women attracted the attention of law enforcement agencies. At the end of 2022, an ‘employee of the Ukrainian Security Service’ began to communicate with Valeriya on one of the messenger services. Around this time, Valeriya had also formed a new friendship with a woman who, in subsequent procedural documents, is listed as a secret witness with the codename ‘Geranium.’ It was ‘Geranium’ who carried out investigative actions against Zotova, entitled ‘Operational Experiment,’ and her testimony was to form the main evidence against Zotova.

After ‘Geranium’ heard from Valeriya that the latter’s ‘Ukrainian’ interlocutors had offered her money to set fire to a military aid collection point, she agreed to take part. It was ‘Geranium’ who found a car and driver for this purpose and accompanied Zotova in this car up to the moment of the latter’s arrest. Zotova claims she did not plan to carry out the arson but wanted merely to pretend to do so to receive the reward. In court, Zotova’s defence submitted as evidence the correspondence between the two women which confirmed Zotova’s version, but the court refused to take it into account. There are numerous details in this case indicating that, from the very beginning of Zotova’s communication with the ‘officer from the Ukrainian Security Service,’ she was the victim of a provocation, which is prohibited by law. Despite this, in June 2023 Valeriya Zotova was sentenced to six years in a general-regime penal colony for ‘attempting to carry out an act of terrorism’ (Article 30, Part 3, in conjunction with Article 205, Part 1).

Without Leniency

While the proportion of women prosecuted on politically motivated charges had been steadily rising, the approach of law enforcement and the judiciary towards them changed dramatically with the start of the war against Ukraine. In prosecutions initiated before the war, women were typically not sentenced to terms of imprisonment, whereas men were imprisoned at a rate two and a half times higher. After the war began, this pattern shifted significantly. In the years 2022-24, nearly half of all criminal prosecutions against women resulted in imprisonment.[3] The previous more lenient treatment of women by law enforcement and the judicial system has rapidly eroded.

Very Different Women

The database of the ‘Political Prisoners. Memorial’ human rights project contains information about 266 women imprisoned as a result of prosecutions with indications of political motivation in 67 regions of Russia and the occupied territories. The highest numbers are found in Russia’s largest regions and in the occupied areas of Ukraine. Of course, this data is incomplete; there is every reason to believe that this is especially so with regard to the occupied territories.

Number of women imprisoned in cases with indications of political motivation by region of prosecution (number of individuals):

| Region/Occupied Territory | Number |

| Moscow | 46 |

| St. Petersburg | 17 |

| Occupied part of Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Oblast | 13 |

| Occupied part of Ukraine’s Donetsk region | 12 |

| Samara region | 11 |

Source: Political Prisoners. Memorial

Women of all ages have been imprisoned as a result of politically motivated prosecutions. Neither youth nor old age appears to be a mitigating factor.

Age of women imprisoned in cases with indications of political motivation (as a percentage):

| Age Group | Percentage |

| Under 18 | 3% |

| 18-21 | 6% |

| 22-30 | 16% |

| 31-40 | 26% |

| 41-50 | 20% |

| 51-60 | 15% |

| 61 and over | 14% |

Source: Political Prisoners. Memorial

The Youngest and the Oldest

The youngest among women imprisoned in cases with indications of political motivation is 15 years old; at the time of her arrest, she was a 14-year-old high school student. Anna has been charged with participation in a terrorist organisation and planning the murder of two or more people. Her case will be discussed in more detail in the following section.

The oldest in this list is Larisa Pashnina, now 86. Despite her age, in October 2023, a court sentenced Pashnina to serve time in a general-regime penal colony. She was most likely associated with the informal grouping ‘Movement of Citizens of the USSR.’ She was convicted, apparently, on charges of abetting terrorist activity (Article 205.1, Part 1) as well as of calling for people to engage in terrorism and the justification of terrorism (Article 205.2, Part 2).

The second oldest is 76-year-old Galina Ivanova, whose case is far better documented.

The Case of Galina Ivanova

Galina Ivanova is a pensioner from St. Petersburg born in 1948. In the autumn of 2023, she was targeted by telephone scammers for over a month, ultimately being defrauded of half a million roubles. Later, ‘FSB officers’ approached her and proposed she participate in an operation to commit arson in order to scare off a criminal. On 15 November 2023, Ivanova set fire to the windscreen of a car parked near a military recruitment centre. The flames were quickly extinguished, causing no significant damage. Ivanova was arrested on the spot; at the time of the arson, she had been speaking to the scammers on the phone.

In January 2025, a court convicted Ivanova of organising a terrorist act that caused significant material damage (Article 205, Part 2) and sentenced her to 10 years’ imprisonment. The telephone fraud case, in which Ivanova has been recognised by the authorities as a victim, is still under investigation.

What Are the Conditions of Imprisonment for Women?

It is widely believed that women in detention face less violence than men. More often, they suffer from the harsh regulations imposed by the administration at the penal facility where they are serving their sentence. For example, in penal colonies, women are required to work intensively, often in hazardous conditions, and to stand outdoors for long periods, including in winter, which is especially detrimental to their health. Complaints about lack of access to hygiene products are also common.

While this assessment is largely accurate, there are more shocking cases that clearly fall outside this general pattern.

Anna’s Case

Anna, a school student from Moscow Oblast, had a passion for dancing and taking part in competitions and was learning to play the electric guitar. She became interested in the history of the Columbine school massacre in the US and subscribed to a related Telegram channel. To join another closed Telegram channel she filled out a questionnaire in which she stated she planned to carry out a shooting at her own school. In November 2023, Anna was arrested and charged with membership in the ‘International Columbine Movement’ and with preparing an attack on her school. The charges were based on her participation in related Telegram channels and a video in which she set off a firecracker. A subsequent forensic examination determined that the firecracker was not an explosive device.

Quiet and shy, Anna was placed in a remand prison for juveniles attached to a penal colony. There, she was systematically abused by her cellmates. She was humiliated, had her head shaved and eyebrows plucked, was beaten, forced to strip, photographed in degrading poses, dunked headfirst in a toilet, doused with urine, and raped with objects. The administration of the remand prison took no action, and the investigator insisted on extending Anna’s detention.

At one point, Anna attempted to take her own life. After this, in an extremely fragile psychological state, she was transferred to a psychiatric hospital, where she remains.

The situation of women prosecuted on political grounds in the occupied territories is a separate and harrowing issue. We conclude with the story of Natalia Vlasova. Formally, the abuse she endured took place in the so-called ‘Donetsk People’s Republic’ before its ‘annexation’ by Russia. However, Vlasova’s conviction by a Russian court in 2024 was on the basis of confessions extracted from her in Donetsk in 2019.

There is ample evidence that illegal prisons in the occupied territories continue to operate even after their formal ‘annexation’ by Russia, and the conditions in these facilities remain shocking, even by Russian standards.

The Case of Natalia Vlasova

Natalia Vlasova, a Ukrainian citizen born in 1981, was arrested in Donetsk in March 2019 and held in the notorious ‘Izolyatsiya’ torture prison. During her trial at the Southern District Military Court in Rostov-on-Don, she described the conditions of her detention and the ‘investigative methods’ used in her case. Here are some excerpts from her testimony in court:

“It was a secret MGB (Ministry of State Security) prison in the DPR. They called it the death factory, and its boss was Yevdokimov. At one point, I also asked to be shot while attempting to escape, but no—Yevdokimov said I should suffer.”

“Yevdokimov personally filed my teeth down with a metal file, twisted my nipples, and tried to insert a bottle into my vagina… Meanwhile, his thugs struck me unexpectedly from all sides.”

“They stripped me, tied me with tape, poured water on me, and applied electric shocks. If I didn’t scream enough, they increased the electric current and the blows became more ferocious. They wanted a reaction, which I didn’t immediately understand. When I screamed loud enough, I heard satisfied voices. A doctor was also present during the torture, and when I lost consciousness, he revived me with ammonia.”

“After the torture, they chained me in a cell with my arms raised overnight. I had no strength left, and it was difficult to stand on my beaten soles, shifting from toe to toe. They also kept me in a basement, where I could only sit or stand — an extremely cramped space. It was unbearably cold, and I was shivering to the bone. They gave me water for an unspecified amount of time — I could only wet my lips so there would be enough to clean other parts of my body, and during menstruation, it was another story — finding pads, or rather using a T-shirt.”

“Fifteen men came to have sexual intercourse with me; they even took me to the shower for this purpose… They were usually drunk.”

“After violating my body, trying to eradicate everything human in me, the least of it was giving me dirty plates with scraps of food, and not taking out the bucket with excrement. They humiliated me in ways that it’s impossible to understand how I endured it all. I didn’t harm anyone, nor did I have any intent to do so.”

“As for the videos broadcast on the Russia-1 TV channel, which were presented as evidence, I’ll briefly describe one day of filming… They took me into a room. First Zakharov dragged me around by my hair, beat me, and humiliated me, demonstrating his strength. He ruptured my eardrum, blood flowed, and air escaped through my ear. When the cameraman arrived, they weren’t deterred, and the madness escalated. The reporter asked them not to do it, saying, ‘Don’t, she’s just a girl.’ Zakharov’s assistant tried to protect me from the blows by covering me with his arms, kissed my head, and said that no one would harm me while he was there. Then he would periodically run out and return with brandy, asking me to drink and calm down — they needed to film, but I couldn’t say a word.”

Vlasova was charged on seven counts, including participation in a terrorist group, espionage, preparing to make an attempt on the lives of law enforcement officers, and preparing to commit a terrorist act. In December 2024, she was sentenced to 18 years and 2 months’ imprisonment.

Women imprisoned as a result of politically motivated prosecutions come from all walks of life. Among them are schoolgirls and students, pensioners, teachers, doctors, journalists, bloggers, beauticians, nurses, IT specialists, cashiers and entrepreneurs. They include a horse-riding instructor, a dog trainer, a tattoo artist, and a janitor in a sports school. Some are champions in Sumo wrestling and powerlifting, others are academics. Many were civil society activists, while others led private lives but ‘believed in the wrong god’ or posted the wrong comment online. Some are mothers raising young children; others are elderly and alone. Many are Ukrainian women who refuse to accept the occupation or who simply caught the attention of the Russian security forces.

All these women are very different from one another; some of them are young girls. The one thing they all have in common is that the authorities, in pursuit of political goals, tore them from their ordinary lives and deprived them of their freedom.

[1] Data from the ‘Political Prisoners. Memorial’ Project and OVD-Info as of 1 March 2025.

[2] These numbers also include cases where the charges are for the preparation, or attempt at commission, of crimes under the relevant articles.

[3] In fact, the proportion of women imprisoned in the years 2022-24 is likely to be even higher. This is because trials on ‘less serious’ charges typically proceed more quickly. As a result, sentences handed down in these cases are reflected in the statistics sooner, while sentences handed down on ‘more serious’ charges appear in the statistics later.